Climate change: a risk soon unsustainable for insurers and policyholders?

A worrying phenomenon has been growing for several years: the gradual withdrawal of insurance companies from the most at-risk areas.

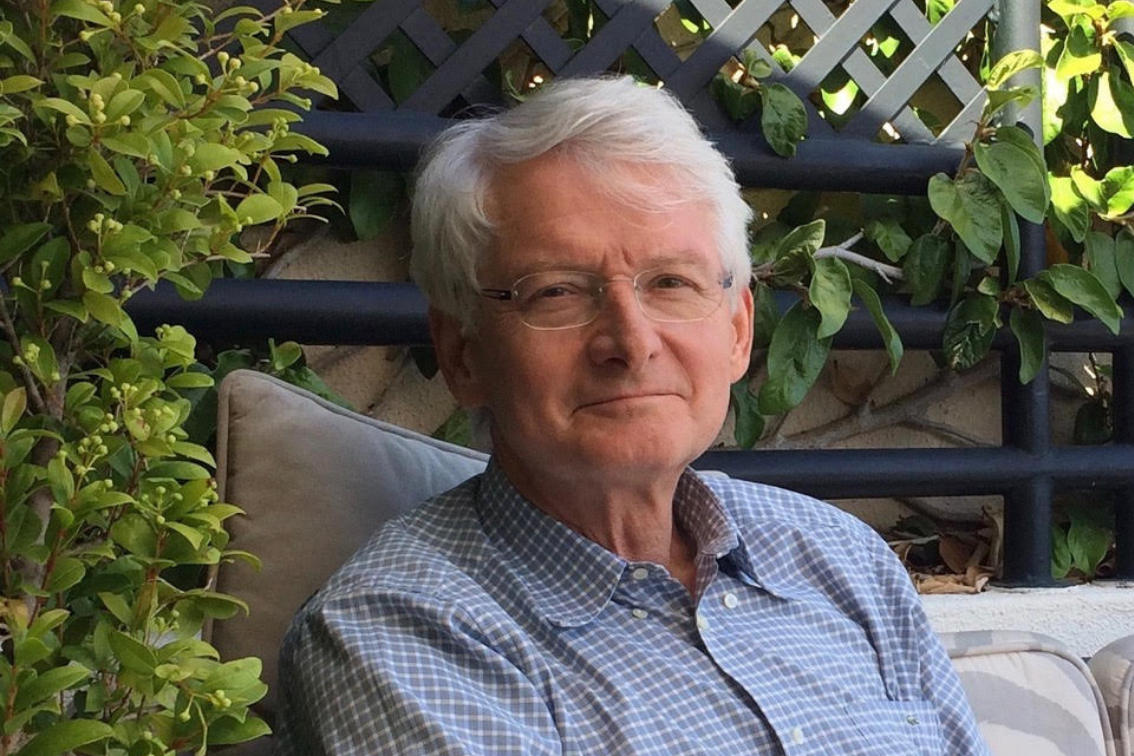

Co-founder and honorary director of the E4S center, Jean-Pierre Danthine deplores Switzerland's lack of ambition in climate policy and its tendency to be short-sighted about its future. Interview

Since his departure from the Swiss National Bank (SNB), where he was Vice Chairman of the Governing Board from 2012 to 2015, Jean-Pierre Danthine devotes part of his time to sustainability issues. He is notably cofounder — with the University of Lausanne, IMD and EPFL — and honorary director of the Enterprise for Society center (E4S), which aims to rethink business and the economy around sustainability, innovation and social responsibility.

At a time when the very reality of global warming is being questioned by some powerful actors, when diplomatic disillusionment and political paralysis succeed one another, issues related to energy, climate and sustainable finance appear more vital than ever. From the COP in Belém to Switzerland’s budgetary choices, through the role of central banks and the financial sector, Jean-Pierre Danthine delivers his analysis of the current blockages and the levers still available. Interview

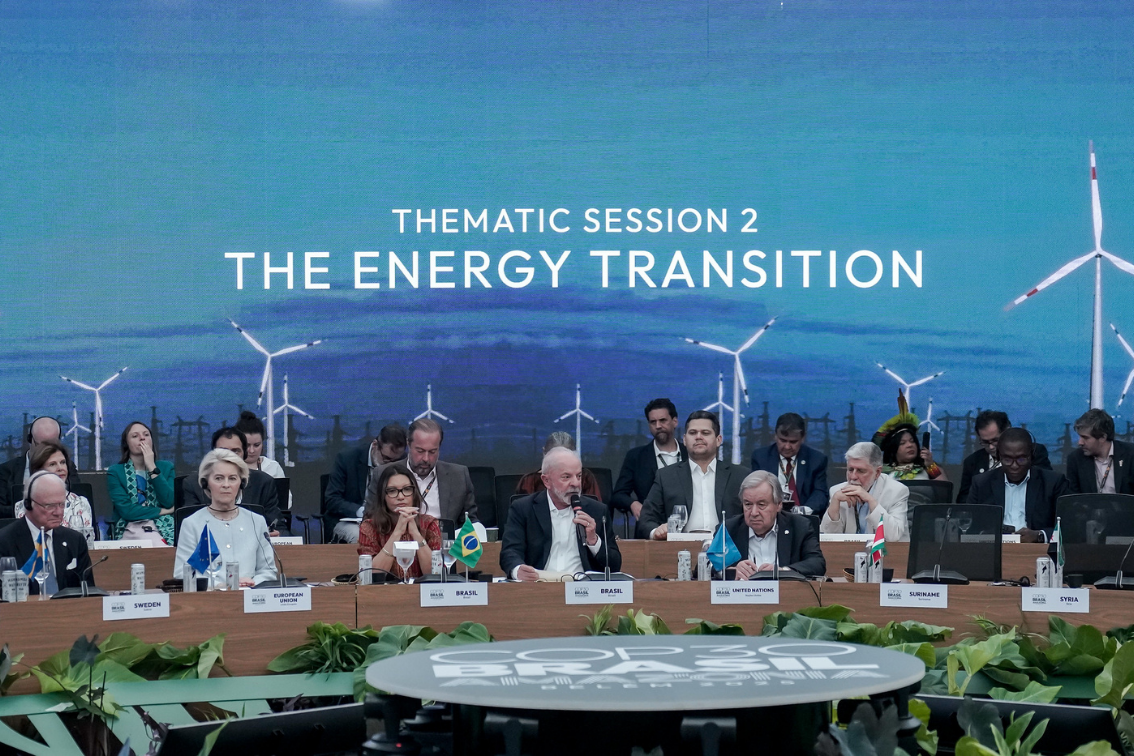

At the last COP in Belém, many thought the big winners were fossil fuels… What is your reaction?

Like many, I remain somewhat disillusioned — even cynical — about that last COP. Concretely, I do not believe it is possible to convince fossil fuel producers to give up their activity as long as there is demand. Proof: even wealthy and advanced countries, like Norway, continue to put new oil fields into production.

To my mind, the only real solution is to reduce our consumption while redirecting the subsidies currently devoted to fossil fuels toward the development of renewable energies.

In Switzerland, the rejection of the CO₂ law has led to a situation in which both the right and the left — for different reasons, to be sure — oppose taxes, even though the financial means are lacking to support the energy transition. Ultimately, this constant political battle leads us to inaction.

Which solution would you endorse?

I remain convinced that the first measure to adopt is to establish a price for CO₂, as many economists recommend. I also place much hope in the European Union’s carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM). By taxing imports according to their CO₂ content, this mechanism would protect the competitiveness of local companies and finally make carbon pricing possible, without the usual argument that it would disadvantage us vis‑à‑vis foreign producers.

But there is already an emissions trading system…

We did start to put a price on CO₂ with the emissions trading market. In principle, it is a very good mechanism. However, its scope remains too limited — many sectors are excluded — and it has remained too localized: each region has its own system, and only Europe has really exercised a leadership role. Switzerland has, moreover, joined the European market.

The more general problem is that this market has been perverted by the pressures of big polluters. They argued that, without free allocations, they would be disadvantaged relative to their foreign competitors. The result: they were given massive volumes of free allowances — so massive that equilibrium prices were far too low. Furthermore, many of them were even able to resell part of them and make profits, instead of being incentivized to reduce their emissions. The price signal was therefore considerably weakened.

It is precisely to remedy this flaw that I place much hope in the CBAM. Once this mechanism is in place, it will finally be possible to more decisively reduce free allocations in the European carbon market, up to their complete elimination. For me, it is a clear project and an essential step for carbon pricing to really work.

Was COP 30 not also a victim of waning public interest in energy and climate issues, both in Trump’s United States and in Switzerland?

Many countries are now faced with a systemic problem: the end of the month weighs more heavily than the end of the world. Purchasing power currently trumps environmental concerns. This is notably the case in Switzerland, where two issues overwhelmingly dominate public debate: the cost of healthcare and that of housing. These are what feed the feeling of dwindling purchasing power, whereas, paradoxically, the Swiss labor market is doing very well and wages are among the highest in the world. Recent data clearly confirm this: real purchasing power has increased and Switzerland is faring much better than most European countries.

As long as housing and health problems are not solved, these concerns will continue to take precedence over energy and environmental ones, even if the climate issue is actually far more decisive for our future. These debates are also muddled by some discourse that downplays the severity of the situation, presenting it as an exaggeration, or — as Trump claims — as the greatest scam of the moment.

Since Paris in 2015, no COP has truly marked its era. Should we continue with these large international meetings?

I am not an expert on all these international mechanisms and I remain fairly skeptical about these large climate gatherings, whose carbon footprint is enormous, too. That said, the climate problem remains a global issue and, to solve it properly, we would need something akin to a world government. States cannot achieve it in isolation. On the other hand, when a grouping is sufficiently large, as is the case with the European Union, it can begin to act effectively.

To my mind, it is clear: solutions must be built at a multinational scale. The example that inspires me most remains that of ozone layer protection. We identified a global problem, gathered around the table, signed a treaty and solved the crisis. It is the only case where environmental multilateralism really worked — of course, partly because the problem was simpler and the geopolitical context was more favorable at the time.

It is not only oil companies who will never commit harakiri: it is everyone. The finding is that humans remain human: if it is costly and the benefit is distant and diffuse, commitment disappears.

Shouldn’t the current format at least be revised?

In terms of an ideal solution, I do not really see another. To address CO₂ and climate change, we need a global agreement — perhaps not with nearly 200 countries as at the COPs, but rather with the main powers, gathered for example within a G7 or G20 framework.

The only real contemporary example of international cooperation that really works is that of central banks. They meet in Basel every two months and one observes a form of coordination that almost resembles a world government, even if, of course, it remains very limited. These are technocratic institutions, with a clear mandate and strict constraints; they cannot do anything they please. But in terms of information exchange, alignment of views and coordination of action, it is a model that works.

Like the disappearance of the Net-Zero Banking Alliance, isn’t the main challenge a financial world turning away from sustainability issues?

Regarding that banking alliance, the question is whether it really had an impact on the economy and companies. In sustainability matters, another question arises: “At what cost?” And here I return to my initial cynicism. It is not only oil companies that will never commit harakiri: it is everyone. As soon as climate action involves a significant financial sacrifice, whether a bank or an industrialist, the observation is that humans remain human: if it costs a lot and the benefit is distant and diffuse, engagement disappears.

That is why I do not think much should be expected from the private sector without strong state intervention. I have already said this very clearly at the Geneva event “Building Bridges”: as long as investors are not ready to accept at least a slight reduction in their returns to finance the transition, it will, for the most part, remain mere fine words.

The slogan “doing well by doing good ” is attractive, and sometimes true — for example in the cleantech sector. But in many cases, prices are distorted: neither carbon nor biodiversity destruction are priced. Therefore, “doing well” often comes down to doing harm, and “doing good” implies lower returns. Refusing to see this reality is self-deception.

So you don’t believe all those experts who claim that investing sustainably doesn’t necessarily require sacrificing returns?

In my view, those sustainable finance specialists are deluding themselves. If we start from that assumption, we cannot truly face the transition. We must acknowledge that, in the short term, sustainability has a cost — and it is precisely the role of the state to assume part of it so that society can move forward.

This public intervention could take several forms. First, it should put all actors on an equal footing. This is, incidentally, what companies like Holcim demand: “Regulate us, constrain us, but constrain everyone in the same way; otherwise, we are no longer sufficiently competitive.”

Authorities should also set up blended financing mechanisms, in which the state assumes part of the risk to allow the private sector to invest honestly, without betraying its clients’ expectations regarding returns and pensions.

The role of central banks in the energy transition is little discussed. Take the Swiss National Bank (SNB), one of the world’s largest investors. Shouldn’t it play a role in promoting more sustainable finance?

That would imply integrating the sustainability issue into the SNB’s mandate, which would therefore require a majority within the Swiss government to be in favor of the idea. Is that the case today? Clearly not — and that is regrettable, because, in principle, the idea is not a bad one. But we live in a democracy: such a change can only happen if there is a genuine majority — among the people, Parliament and the government — in favor of having the National Bank take up this issue.

If, one day, that majority exists, then yes, we can begin to discuss it. But it must be done intelligently, respecting a fundamental condition: never weaken the SNB’s primary mandate, which is to guarantee price stability.

Acting intelligently, what does that mean? First, recognizing that some widely circulated ideas do not work. We know very well, for example, that simply excluding a stock from a portfolio changes nothing in reality. Finance alone cannot turn off the emissions tap: overall, that strategy has no effect.

On the other hand, one can ask an investor the size of the SNB to do what the Norwegian sovereign wealth fund does: become an active investor, intervene in general meetings and push companies to adopt more ambitious transition strategies. That seems to me far more useful than excluding certain companies to ease one’s conscience.

Respecting the debt brake in the name of future generations, while we could make investments that would protect them even better in the long term, is a contradiction.

Through part of the SNB’s funds, should Switzerland follow Norway’s example and create its own sovereign wealth fund?

Creating a fund, whether via the SNB or using public money, is not simple. You cannot create a fund out of nothing: you need seed capital. Otherwise, the only solution would be for the state to go into debt to finance it, and I don’t think that is its role.

The idea currently being discussed is rather to ask whether it would be possible to transfer part of the SNB’s balance sheet into a separate fund, completely independent from it. That assumes, first, that the SNB is not able to reduce its balance sheet — such a reduction being the “first best.” Next, this option would only make sense if this fund could be managed differently, with greater return ambition and, possibly, sustainability objectives.

To be perfectly honest, I was very hostile to this idea at first. I am starting to think about it a little more now, but I still do not see a simple solution. Above all, it is absolutely essential to ensure that this does not in any way undermine the SNB’s independence or its ability to conduct monetary policy. Finally, one would have to ensure the establishment of an institutional framework guaranteeing management of this fund free from partisan political influence.

Switzerland is ambivalent about its own climate policy. Are we lacking ambition in our country, with 2035 targets already judged unattainable?

Yes, I clearly think we lack ambition and that we are short-sighted. With more ambition today, we could actually pay much less tomorrow. I tried to demonstrate this before a parliamentary committee, without success.

This lack of political ambition regarding the energy transition is all the more regrettable because Switzerland has a magnificent tool: the debt brake. Thanks to it, our country is in a privileged position in international comparison. Today, however, it becomes necessary to recall its primary objective, which is to protect future generations.

If we make significant investments now — which would temporarily exceed the limits of the debt brake — but these investments prove beneficial, and indirectly profitable, for the future, then future generations will gain much more than if we remain strictly attached to the original framework.

In other words, respecting the debt brake in the name of future generations, while we could make investments that would protect them even better in the long term, is a contradiction. The debt brake must remain a tool, not a dogma. From this perspective, and subject to strict and nonpartisan scientific control, we should today mobilize much greater resources to:

— rapidly renovate the building stock;

— transform individual mobility;

— finance measures to adapt to climate change.

And support start-ups and companies active in cleantech?

Indeed, this is one of the areas in which we can contribute decisively. Switzerland has top-tier universities capable of creating meaningful jobs. Young people who engage in these fields know exactly why they do it: they contribute to a global common good. And for our country, it is all benefit.

I greatly appreciated an article in The Economist about electric vehicles and China. People often say that cleantech “costs a lot,” but China demonstrates precisely the opposite: it has, for example, made its massive investment in electromobility a true economic model and is today winning on all fronts. It has taken several steps ahead and is already reaping the industrial and geopolitical rewards.

It is a perfect illustration of the principle “doing well by doing good .” In cleantech, it is probably where we have the best chance to reconcile economic performance and positive environmental impact. It is in this type of strategy that I see the real prospect of success: creating value by doing what is good for the climate.

The planned budget cuts in Bern do not really go in that direction…

After having worked extraordinarily well over the past decades, our government does not realize how much the world has changed. We have entered a new era, and it is no longer enough to imagine that what worked perfectly in the past will continue to work the same way in the future.

A profound questioning becomes indispensable in Switzerland, and I unfortunately do not see it coming. And this does not concern only the environment and energy: it is just as true for our industrial policies, for our way of conceiving the functioning of our economy, for our relationship to innovation and risk. Many things deserve to be rethought in depth and without prejudice.

I understand that this effort is difficult: when a country has enjoyed such success for so long, it is natural to think it is better not to change anything. But if we do not make this effort to adapt, I fear that we will face much more difficult years ahead.

This article has been automatically translated using AI. If you notice any errors, please don't hesitate to contact us.